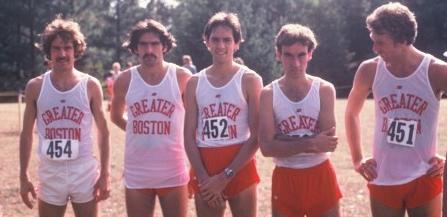

Bill Squires, Bill Rodgers, and GBTC

Club Feature: Greater Boston Track Club

By Barbara Huebner

Resource Guide 2004, Vol. 11, No. 5

American Track & Field

It was early on a Thursday morning in April 1977 when Randy Thomas aimed his ’76 Toyota Celica down Route 2 toward Boston. Two of his Greater Boston Track Club teammates would be waiting in a parking lot on Route 128 for Thomas to collect them on the way to the Penn Relays, where they would compete that night.

But a wheel bearing broke, and Thomas was two, maybe three hours late and $170 in repairs poorer by the time he reached his passengers. With only $30 in his pocket and no margin for error in getting to Philadelphia, they hit the road again, made it to the meet on time, barely, and all ran PRs.

After a night of sleep in a shared hotel room, made into a triple courtesy of a mattress on the floor, the guys woke to an inspiration: let’s stay another night so we can watch the meet tomorrow. Yeah, I know we don’t have enough money left but let’s do it anyway. Sneaking out of their hotel room at 5 the next morning because they had no money to pay the bill, they bought a package of bologna and a loaf of bread from a convenience store. Adding mustard from a hot-dog stand at Franklin Field, they sat in the upper deck of the stadium all day, watching the meet and eating bologna sandwiches. Life was good.

Which is how the Celica came to be parked in the far left lane going on to the Ben Franklin Bridge heading out of Philly that evening while its occupants, three esteemed members of the Greater Boston Track Club who had just the day before all run the fastest races of their lives, crawled out to scoop up all the loose change they could find on the ground so they could pay the toll. Richer by $5 or $6, they resumed the trip. When they got to the Garden State Parkway, they got out again and scavenged for gas money. This time the take was only $4, but it was enough.

The trio got back to the Eliot Lounge, near the Boston Marathon finish line, about 1 a.m., split one Miller Lite three ways with their last $1.50, and went home happy.

Thomas tells the story to illustrate a point: that runners were hungry then in a way that fueled their competitive fires. You did whatever it took.

But in a broader sense, it gets at the heart of the phenomenal success of the Greater Boston Track Club in the late 1970s, a success made most public when four of the top 10 finishers in the 1979 Boston Marathon came from its membership rolls. You did things together that you would never do alone. You shared what you had. You kicked around ideas. And you succeeded.

The GBTC was founded in 1973, when senior Jack McDonald gathered a half dozen guys (Bill Squires, Bob Sevene, Don Ricciato, Kirk Pfrangle, Dick Mahoney and Dave Elliott, by most accounts) in a locker room at Boston College to assess interest in forming a track club for the post-collegiate runner. McDonald, a 4-minute miler, had just finished hastily putting together an exhibition track meet between a visiting Oxford-Cambridge team and a group of New England all-stars, and so enjoyed the experience – both athletic and social – that he wanted to repeat it on a regular basis.

“There might have been a six-pack of beer floating around at that meeting,” recalled McDonald, now the athletics director at Quinnipiac College in Hamden, Conn.

They immediately enlisted Squires, track coach of the successful Boston State College program, to coach. Squires remembers a slew of names bandied about, including the Codfishers and Boston Beaners, before the settled on Greater Boston Track Club. In the fall of 1973, a promising young distance runner named Bill Rodgers joined the group. A year later, Rodgers would be the upset winner of the 1975 Boston Marathon, wearing a singlet with “GBTC” written by hand across the front. Two legends were born that day, one wearing the name of the other.

Before the success ebbed in the early 1980s, the GBTC would go down in history as one of the greatest-ever amateur distance running clubs in the world. On its resume:

* Three of the top 5 finishers in the 1978 Boston Marathon (1. Rodgers, 4. Jack Fultz, 5. Randy Thomas)

* Four of the top 10 finishers in the 1979 Boston Marathon (1. Rodgers, 3. Bob Hodge, 8. Thomas, 10. Dick Mahoney)

* More than 20 New England titles at various distances from 1973-1980; six consecutive U.S. 25K road racing team titles beginning in from 1974- 1979

* Nine consecutive U.S. 20K titles

* And, in a performance perhaps even more brilliant than that at the Boston Marathon earlier that year, the 1979 Senior Men’s National Cross Country team championship, with GBTC runners going 1-2-4-5- 12 and outscoring the second -place team 26-179.

Scoring at that 10K meet were: 1, Alberto Salazar (30:37); 2, Bob Hodge (30:52); 4, Dan Dillon (30:56); 5, Greg Meyer (31:01); 12, Randy Thomas (31:23).

Perhaps more startling are the names of two men who ran for GBTC that day but didn’t score – Pete Pfitzinger, who would go on to become a two-time Olympian in the marathon; and Bruce Bickford, who in 1985 would be ranked #1 in the world at 10,000 meters before going on to the 1988 Olympics.

“There was so much depth,” said Rodgers, the ace who didn’t even run in the meet.

Think of it as the running-world’s equivalent of “The Perfect Storm,” with a rare combination of factors creating the ideal training environment. Alter one element – Squires, Rodgers, the strong supporting cast always nipping at his heels, the locale, the decade – and it amounts to nothing more than your average rainstorm with an occasional gust of wind.

Start with Squires.

“If you look at most of the great athletes, they all had a coach they believed in and they did what they were told,” said Meyer, who would win the 1983 Boston Marathon and is still the last American man to do so. “When that coach tells you you’re ready, you believe them.”

Squires, himself a three-time All-American miler out of Notre Dame, liked to play around with training, surprise his athletes, make any situation as fun as it was competitive. With the belief that repetition and familiarity are keys to success, he had his athletes doing hill workouts on Heartbreak Hill so they’d still be able to lift their legs once they got tired, and running from Boston College out to Wellesley and back along the Boston Marathon course so they would know how to race every inch of it. Whatever the exact race situation was going to be, whether on the track, cross-country or the roads, Squires wanted his athletes to be prepared.

“We did it so many times,” said Squires, “you could do it in your sleep.”

That’s one of the rare Squires sentences that is clear from start to finish. Listening to the man known around Boston simply as Coach is akin to chasing butterflies. Just when you think his thoughts have finally been captured in your flailing net, you look up to see them flutter away. No matter. He manages to get his point across, although you’re never sure how.

Tom Derderian, who ran for Squires at the time and now coaches the GBTC, described Squires’ typical delivery of instructions for a track workout. “He’d say ‘go there and go there and go ugh and then ugh and then ugh. OK?’ And everyone said ‘OK.’ Everyone knew you came there to run hard.”

“He was just the right guy to lead us,” said Rodgers. “He wasn’t authoritarian and he wasn’t laissez faire; he was right in between. He was quirky the way runners are quirky.”

Talk to his top athletes of the days, folks like Rodgers and Meyer and Hodge, and it’s no specific workout they recall. It’s a feeling. Squires believed in moderation on the track; he believed that marathon success begins at the 10K; he believed in his novel workout called “the simulator,” – intervals on the Boston College track followed by a run on the nearby Newton Hills followed by another track workout; he believed that a coach needs to control where and when his athletes race. But above all, he believed in the importance of belief and the courage to think big.

His athletes returned that belief. “We put our total faith in him, and we achieved,” said Sevene, now the coach of Team USA Monterrey.

“Thinking big” was all that much easier with Rodgers around. At the time he joined the GBTC in 1973, Rodgers – after a year of joblessness – was working as an attendant at the Fernald School, helping tend a ward of moderately-retarded men. He would often run with Sevene, who lived nearby. After running some in high school and college, he was just starting to get his running back together after foundering since graduation. He had even quit entirely for awhile.

But in less than two years under Squires and surrounded by his GBTC teammates, Rodgers would finish third at the 1975 World Cross Country Championships, and shortly thereafter win the 1975 Boston Marathon in 2:09:55, an American record.

That’s when things really took off. With Rodgers as a magnet, the club quickly drew the rest of the region’s top distance runners and eventually a few from outside New England, as well. But the internal effect was more dramatic. Rodgers, after all, had run just 2:19:34 at Boston in 1974. His GBTC teammates now looked at him and said: Wait a minute. I can hang with him in workouts. If he can run 2:09, I can run 2:11.

“I don’t think people give enough credit to Billy for the confidence he gave to American distance running,” said Thomas, now the head track coach at Boston College.

Plus now you had a core of runners able to push Rodgers. “Billy knew if he screwed up, Randy would get him and gloat about it,” said Derderian.

Then there was the trickle-down effect. Before the 1979 Boston Marathon, Bob Hodge was asked by a Brockton Enterprise reporter how fast he hoped to run. When Hodge (whose PR was 2:28) said 2:15, the reporter asked what made him think he could do such a thing. “Randy ran 2:15 last year in New York City, and I run with him,” was the answer.

Had Rodgers been more ego-driven, the whole thing might have fallen apart. But the affable Rodgers had – still has — a certain openness, a generosity of spirit. If you’re a mid-packer in the East McKeesport 10K and bump into celebrity guest Bill Rodgers in the elevator of the headquarters hotel, he’s going to ask you how your race went and he really wants to know. That’s how he was with his teammates, too. “Billy’s the kind of friend, if he couldn’t go to a race he’d throw your name out so maybe they’d take you,” said Meyer, who moved from Michigan to join the GBTC after Rodgers gave him a job at his running store.

In turn, there was scant jealousy of Rodgers’ fame and success.

“I didn’t mind when people said Billy was a better athlete,” said Meyer. “Hell, he was.”

Even the era itself couldn’t have been more ideal. In the Vietnam-laden climate of the mid-to-late 1970s, a lot of young Americans were “finding themselves.” It was acceptable to hang out for awhile after college, try to figure out what to do with your life, explore some personal options. No one jumped from graduation into $80,000-a-year corporate positions; no one got impossibly wealthy overnight from an internet startup. No one needed to: even in Boston, apartments were cheap, especially if you piled in three or four guys. You might be poor if you chose to be a runner, but you weren’t going to be much poorer than you would have been anyway.

“To become a distance runner is more of a gamble today,” said Rodgers, of those low-pressure, no-prize-money days. “The push to make money is on now more than ever in society. We didn’t have as much to lose.”

Bobby Hodge is a good example. In 1977, in the midst of an All- American career at the University of Lowell, Hodge decided to leave school and travel around the country living out of a van, keeping his running low-key (which, to him at the time, meant running twice a day), trying to decide where he wanted to go with his career and his running. By the time the trip ended in March of 1978, he writes on his website, “The decision I came to on this trip was that no matter what else I did, I would run and find out what I could do in the sport until I was either beaten down or successful enough to be satisfied.”

In early 1979, Hodge was working in a shoe store in Hanover, Mass., sleeping on a mattress in its basement and using a garden hose strung outside as a shower. In April of that year, he would finish third in the Boston Marathon.

“I was willing to be just a running bum for a couple of years,” said Hodge, now a law librarian. “[Most guys now] think it’s putting their life on hold. I hate that. How can they view that as sacrificing? They’re living large.”

All this did not go unnoticed in Boston, with its deep distance-running tradition, plentiful collegiate track programs, knowledgeable fan base and such exhaustive news coverage that Joe Concannon of the Boston Globe used to report the results of Thursday night workouts.

“The community of Boston respected the athletes,” recalled Meyer.

“They knew running. You felt like an athlete in Boston. You’d go out for a run and you’d have the guys coming up out of the manhole covers saying, “kick their ass, Billy.”

On April 16, 1979, Rodgers ran 2:09:27 for his third Boston Marathon victory. No one was surprised. Randy Thomas came in eighth, in 2:14:12. No surprise there, either. But Bob Hodge bursting forth with a 16-minute PR to finish third, in 2:12:30? Dick Mahoney, a mailman, running 2:14:36 for 10th?

With four finishers in the top 10 “of probably the finest marathon field ever put together, the Greater Boston Track Club is THE marathon club,” wrote Steve Harris in the next day’s Boston Herarld-American. The city honored the quartet in a ceremony at historic Faneuil Hall.

Their times have stood the test. Had they run them at the 2003 Boston Marathon, Rodgers still would have won. Hodge, Thomas and Mahoney would have come in fifth, seventh and eighth.

It has not been forgotten, but can it be repeated? In the early 1980s, shoe companies lured many of the GBTC’s top guns away to compete for them, a scenario repeated around the country. The club system faded. American distance running, for the most part, suffered for its runners’ relative isolation, until things deteriorated to the point where the U.S. was represented by just one male and one female marathoner at the 2000 Olympics. Enter: the past. Team USA, the Farm Team and others stepped up in an attempt to turn things around.

“Certainly the Greater Boston Track Club is a huge role model for what we do here,” said Keith Hanson. His Hanson’s-Brooks Distance Project in Rochester Hills, Mich., was founded in 1999 and was perhaps the biggest story of the recent U.S. Men’s Olympic Trials when it saw its runners go 4-5-13. The fourth-pace finisher, Trent Briney, was a virtual unknown before the Trials, what Squires would have called a “guppy,” and his 2:12:34 was a PR by 8:36.

Echoes Sevene, who calls himself a reflection of everything Squires was trying to do: “We’re trying to go back today to what that club was.”

Next thing you know, their guys will be eating bologna sandwiches and diving for toll-booth change.

Barbara Huebner wrote about running for the Boston Globe from 1993-2001. She is now a freelance writer and media consultant.